A few years ago, Shalin Shah watched a documentary that featured Nepali eye surgeon Sanduk Ruit, who had traveled to North Korea to perform surgery on thousands of cataract patients living in poverty.

“The idea,” he says, “that one man could bring so much positive change really inspired me to do something.”

And he has. Shalin, now a senior at Tesoro High School in the Capistrano Unified School District, has built a smartphone app that helps blind users take pictures of documents or objects and then reads aloud written words from the photos. It’s called Voice, and it’s available through Apple’s online store.

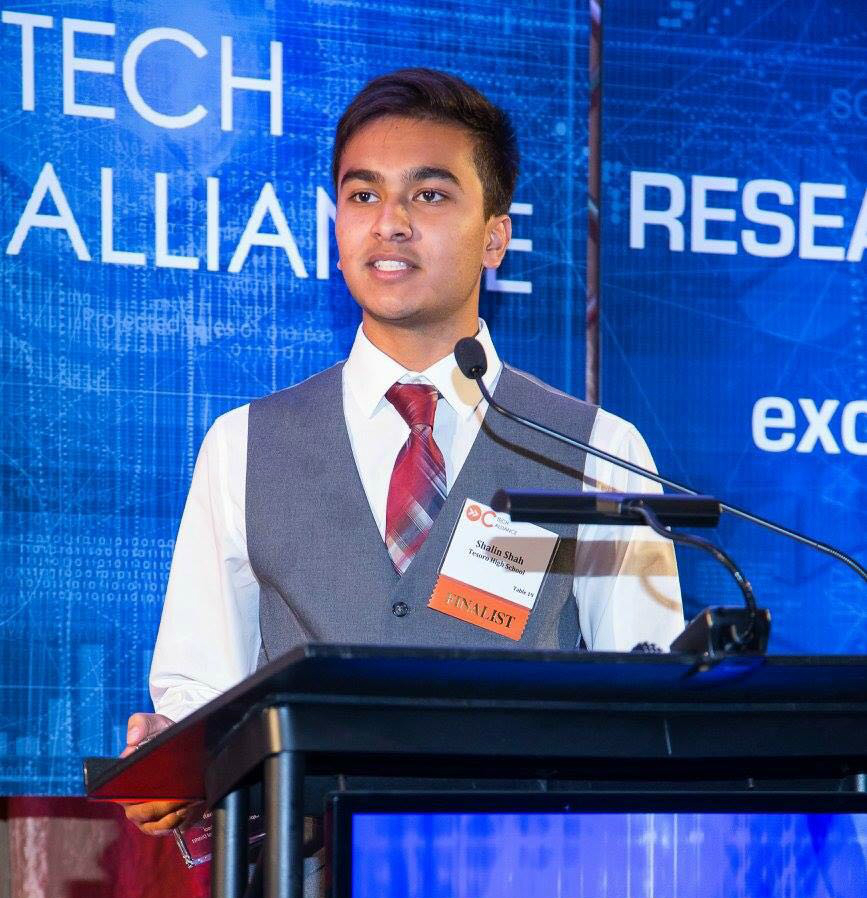

For his efforts, the 17-year-old received the 2016 Innovation in Education Award in the category of Emerging Student Innovator of the Year in Science, Math & Technology. It includes a $2,000 college scholarship.

Presented by Project Tomorrow and the Orange County Technology Alliance and sponsored by OCDE, the Innovation in Education Awards are annually presented to schools, educators and high school students who are charting new paths in education. This year’s other Innovation winners are Tustin Ranch Elementary School in the Tustin Unified School District and teacher Scott Rosenkranz from Sunny Hills High School in the Fullerton Joint Union High School District.

Shalin, who started working on the app when he was in the ninth grade, didn’t set out to win any awards, nor is he taking a profit from the Voice app. His goal all along has been to help people.

“Consider the difficulties blind people have with reading everyday items such as expiration dates on foods, medicine labels and restaurant menus to name a few,” he says. “This routine content is not available in braille or audio.”

Moreover, he adds, fewer than 10 percent of blind Americans can read Braille, and many cannot afford expensive assistive tools.

Shalin says he’s been passionate about technology for most of his life, but at age 12 he became obsessed with programming and would read Internet tutorials for hours at a stretch. When his family visited the local bookstore, he would find the programming section and “devour as much as I could.”

He’s spent the past two years developing Voice, bumping up against a number of challenges along the way. But he continues to refine the app, meeting regularly with those who would benefit from its services to solicit feedback and better understand how they use their iPhones.

He’s spent the past two years developing Voice, bumping up against a number of challenges along the way. But he continues to refine the app, meeting regularly with those who would benefit from its services to solicit feedback and better understand how they use their iPhones.

Meanwhile, since the app went live, Shalin has shared it with numerous senior centers and prominent blind institutes, including the Braille Institute of America and Blindness Support Services.

“These places help thousands of blind people find assistive tools to improve their lives,” he says. “Unfortunately, most tools cost hundreds to thousands of dollars, and out of necessity, blind people buy them even if they cannot afford them. But as more institutions become aware of Voice, my hope is that blind people can use my free solution instead.”

To date, Voice has already been utilized by about 50,000 people who have scanned about 500,000 images, says Shalin, who hopes to promote it globally.

“My desire is to improve the lives of thousands more,” he says. “Although I can’t travel to North Korea to operate on cataracts patients, I hope that through Voice, I can make at least some difference in the blind community, just like my hero Sanduk Ruit.”